An mRNA shot that helps the immune system hunt many cancers

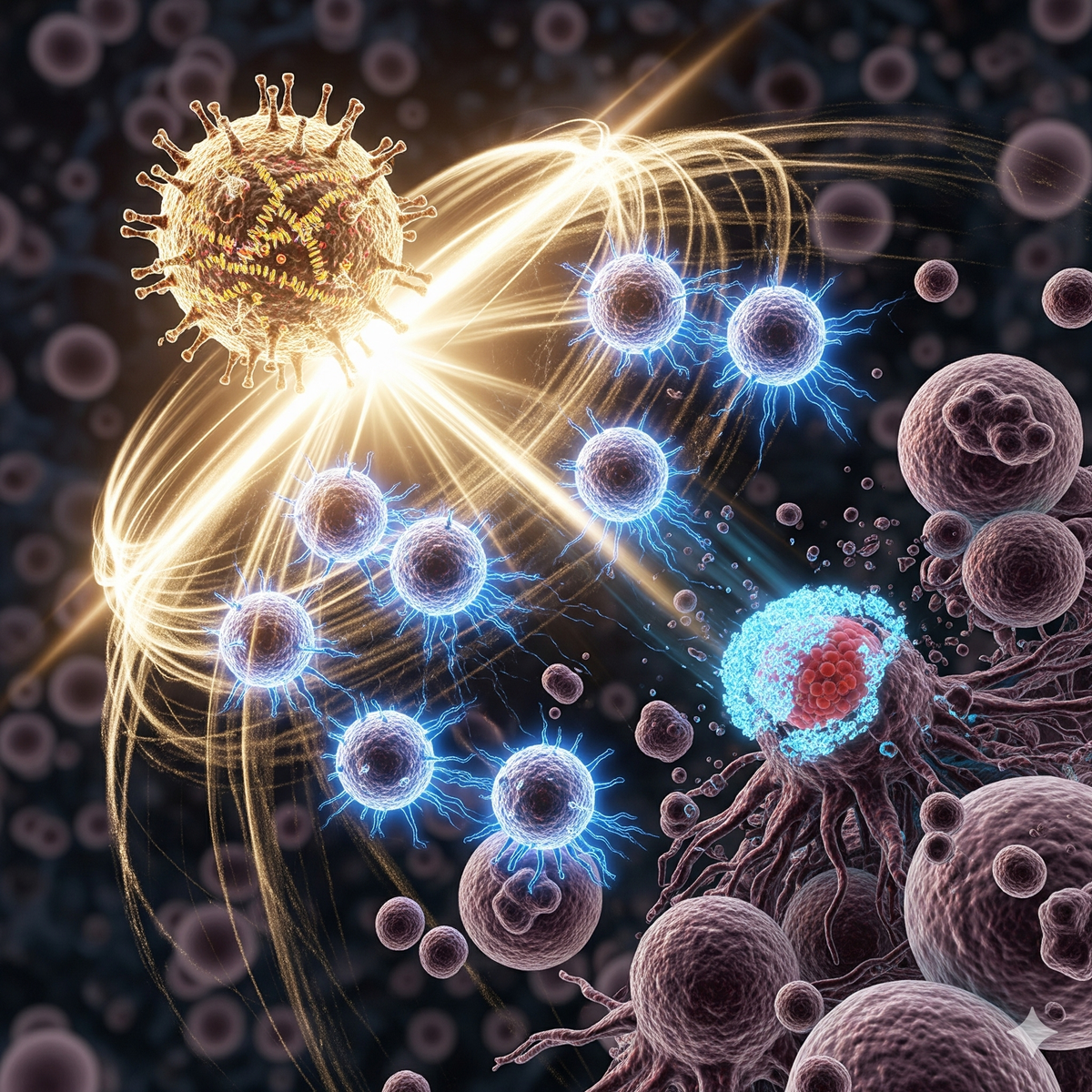

Scientists at the University of Florida say they’ve built an experimental mRNA cancer vaccine that does something many therapies struggle to do: wake up the immune system so it can find and fight tumors across the body—without chemo, radiation, or surgery in preclinical studies. If this approach holds up in humans, it could mark a turning point for how we treat cancer. Source: Nature Biomedical Engineering

what makes this vaccine different

Most cancer vaccines try to teach immune cells to recognize a specific tumor antigen (a unique “molecular face” found on a cancer). That often means lengthy personalization and mixed results when cancers evolve or hide their markers.

The University of Florida team took a different tack. Their mRNA–lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations don’t aim at one tumor-specific target. Instead, they deliver RNA that triggers a strong, early “antiviral-like” alarm inside the body—specifically, a type-I interferon (IFN-I) response. In plain terms, IFN-I is a rapid, innate immune signal that tells surrounding cells “something dangerous is here.” When that alarm sounds near a tumor, it can flip a “cold” tumor (invisible to the immune system) into a “hot” one (highly visible and attackable). Source

A helpful side effect: once the immune system is activated, it can broaden its target list, a process called epitope spreading. Rather than recognizing just one tumor feature, T cells start recognizing many—making relapse and immune escape harder. This early innate jolt can also increase the tumor’s reliance on immune “brakes” like PD-1/PD-L1. That’s useful, because drugs that block the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway (checkpoint inhibitors) work best when those brakes are engaged. Source

– Quick definitions:

- mRNA–LNP: a tiny fat bubble carrying genetic instructions (mRNA) that cells read to make short-lived signals or proteins.

- type-I interferon: an early alarm that mobilizes antiviral and antitumor defenses.

- PD-1/PD-L1: a checkpoint “handshake” cancers use to tell T cells to stand down. Drugs that block it can re-energize cancer-fighting T cells.

what the data show so far

In mouse models (including aggressive B16 melanoma and GL261 glioma), the UF team reports that boosting early IFN-I:

- Sensitized tumors to PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors, converting some “non-responders” into responders.

- Drove epitope spreading, broadening the immune attack beyond any single cancer antigen.

- Enabled direct antitumor activity in certain multi-load mRNA formulations, with some animals showing durable control and protection upon tumor rechallenge.

- Reprogrammed the tumor microenvironment toward immune attack, including effects in the lungs where tumors often spread.

- Produced long-term survival benefits even in animals near humane endpoints. Source, PubMed

In preclinical tests, the same general tactic showed promise across melanoma, brain, bone, and skin tumor settings—without needing tumor-specific personalization and without combining with chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery in those models. That doesn’t mean it’s “side-effect free” in people; rather, it shows antitumor activity can emerge from immune reprogramming alone in animals. Human trials are needed to confirm safety and efficacy. Source

a closer look at the breakthrough

- Mechanism matters: When the researchers blocked IFN-I signaling (for example, using IFNAR1 blockade), the benefits largely disappeared. That points to early IFN-I as a master switch for making tumors visible and responsive. Source

- Transferable immunity: In some models, immunity induced by the vaccine could be transferred to otherwise resistant tumors, suggesting a systemic, teachable response rather than a narrow, local effect. Source

- Synergy with today’s best tools: By heightening the tumor’s dependency on PD-1/PD-L1 signaling, the vaccine appears to lift checkpoint therapy into settings where it usually fails. Source

why this matters

- Off-the-shelf potential: Unlike personalized neoantigen vaccines that require bespoke manufacturing, a generalized mRNA primer could be produced at scale, stored, and shipped widely—critical for community hospitals and resource-limited settings.

- Broader eligibility: Many patients never qualify for checkpoint inhibitors because their tumors are “cold.” Priming with IFN-I could expand who benefits.

- Lower toxicity pathway: In animals, antitumor effects emerged without chemo or radiation, pointing to combinations that might reduce overall treatment burden.

- Faster iteration: mRNA platforms can be rapidly retooled and manufactured, as shown during COVID-19 vaccine development.

meet the team behind the study

The work—by Qdaisat, Wummer, Stover, and colleagues led by Elias J. Sayour at the University of Florida—documents how early IFN-I amplification can unlock checkpoint therapy and drive epitope spreading across multiple models. Sayour’s group focuses on translating RNA and cellular immunotherapies, especially for hard-to-treat brain tumors in children, and this paper lays a mechanistic foundation for clinical testing. Source

what this isn’t (yet)

- A proven human therapy: All results so far are preclinical. Safety, dosing, durability, and biomarkers of response must be established in people.

- A cure-all: Some tumors may still evade or suppress immunity, and overactivation of innate responses can carry risks (inflammation or autoimmunity). Careful trial design and monitoring are essential.

questions to watch as trials begin

- Timing: Is there a “sweet spot” to deliver the IFN-I primer—before, during, or after checkpoint therapy?

- Biomarkers: Which blood or tissue signals best predict who will respond (e.g., baseline interferon signatures or T-cell infiltration)?

- Combinations: Could the primer pair with targeted therapies, oncolytic viruses, or radiation “bursts” that release tumor antigens without full-dose toxicity?

- Durability: How long does epitope spreading last, and does it protect against relapse or metastasis months to years later?

the bottom line

The University of Florida team’s off-the-shelf mRNA approach reframes cancer vaccination: instead of chasing a moving target, it rallies the immune system first, then lets it learn the tumor’s playbook. In animals, that shift turned non-responders into responders, broadened tumor recognition, and in some cases controlled disease without conventional therapies.

If confirmed in people, this strategy could expand access to effective immunotherapy, reduce toxic combinations, and offer a faster, cheaper way to turn “cold” tumors hot—especially in community settings where personalized vaccines are out of reach. The next step is the most important one: rigorous clinical trials to test safety, dosing, and real-world benefit. The question now is not whether we can wake the immune system—but how far we can guide it.

—

Original source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41551-025-01380-1